Holistic Management for Horse Properties – Part 3

Four ecosystem processes

Published in the Horses & People Magazine & Hoofbeats Magazine

By Mariette van den Berg, BAppSc. (Hons), MSc. (Equine Nutrition)

As horse owners, we care for large herbivorous animals. To be able to support horses with the food that they are designed to eat, we must take care of our land. In turn, to be able to make the right decisions and create healthy pastures and adequate food for our horses (and for ourselves), we must understand our global ecosystem and its functions.

As horse owners, we care for large herbivorous animals. To be able to support horses with the food that they are designed to eat, we must take care of our land. In turn, to be able to make the right decisions and create healthy pastures and adequate food for our horses (and for ourselves), we must understand our global ecosystem and its functions.

In order to work with nature’s inherent complexity, we focus on the four fundamental processes that operate in any ecosystem: water cycle, mineral cycle, solar energy flow, and community dynamics (the patterns of change and development within communities of living organisms).[1] Consciously modifying any one of these processes automatically changes all of them in some way because, in reality, they are only different characteristics of the same thing.[2] A useful analogy is that of four different windows into the same room. We observe our ecosystem as it functions from four aspects.

An effective water or mineral cycle or adequate energy flow cannot exist without communities of living organisms, and vice versa. If we want to change the water cycle on a piece of land, for example, we also need to plan which tools to use and how to use them.[1,2] But before going further, we need to consider how those tools might affect the mineral cycle, energy flow, and community dynamics. All of us — not only people who directly manage land — must begin to acquire a basic understanding of the fundamental processes through which our ecosystem functions, if only to better understand our dependence on them.

1.1.1 The four ecosystem processes:

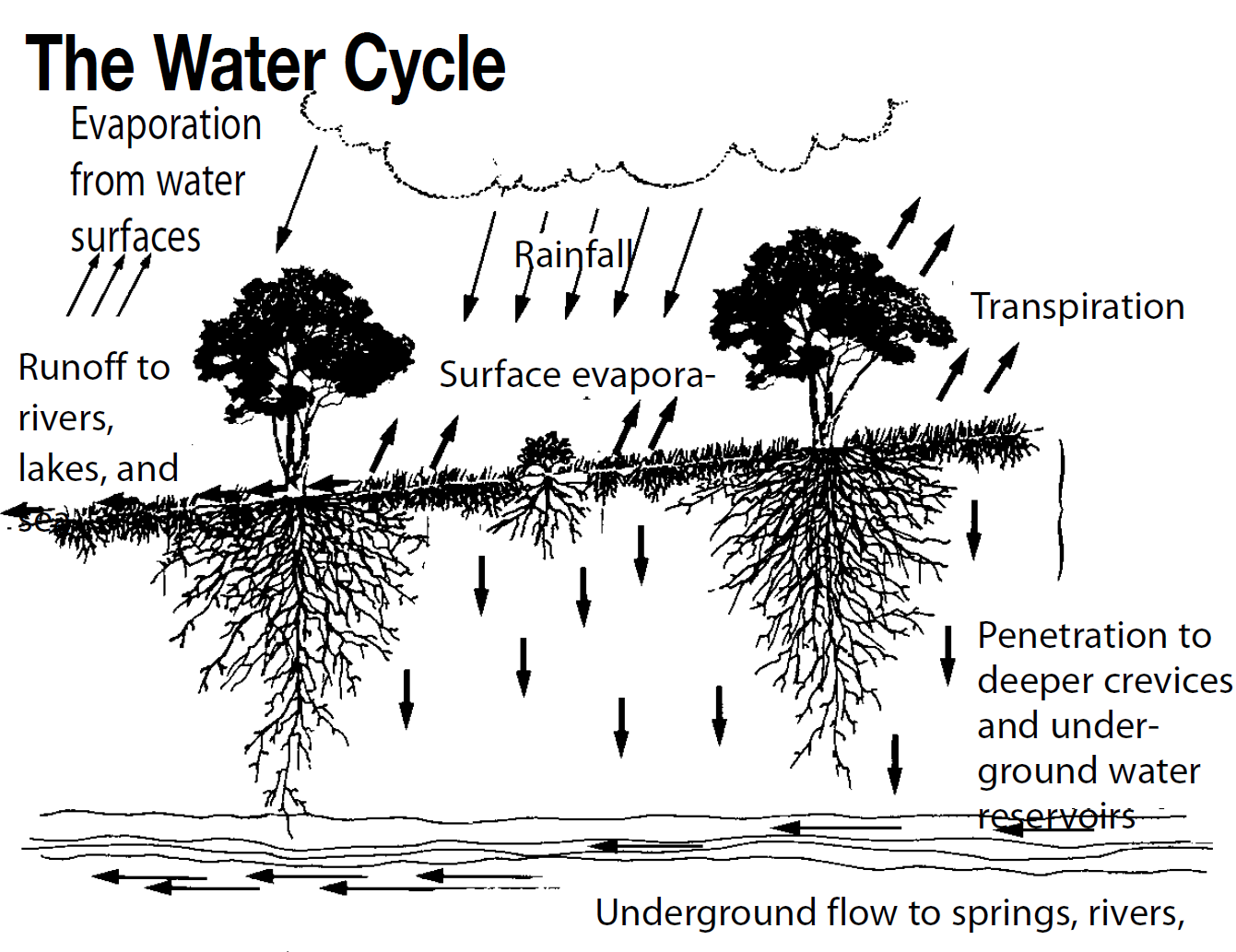

Figure 1. An effective water cycle requires a covered and biologically active soil. When effective, most water soaks in quickly where it falls. Later, it is released slowly through transpiring plants, or through rivers, springs, and aquifers that collect, through seepage, what the plants do not take. However, when soil is exposed and biological activity reduced, most water runs off as floods. What little soaks in is released rapidly from evaporation, which draws moisture back up through the soil surface.

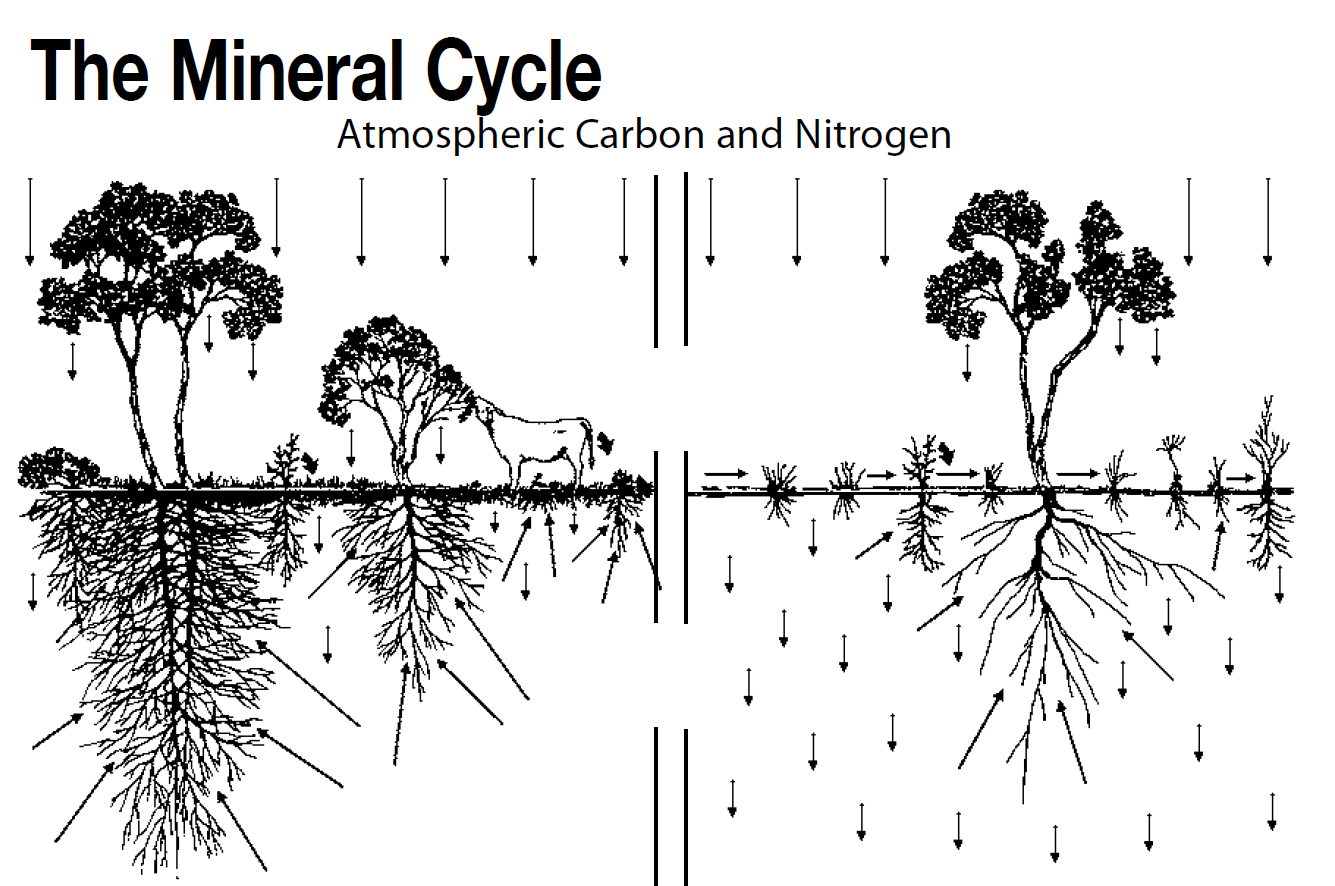

Figure 2. An effective mineral cycle also requires a covered and biologically active soil. When effective (left), many nutrients cycle between living plants and living soil continually. When soil is exposed and biological activity low (right), nutrients become trapped at various points in the cycle or are lost to wind and water erosion.

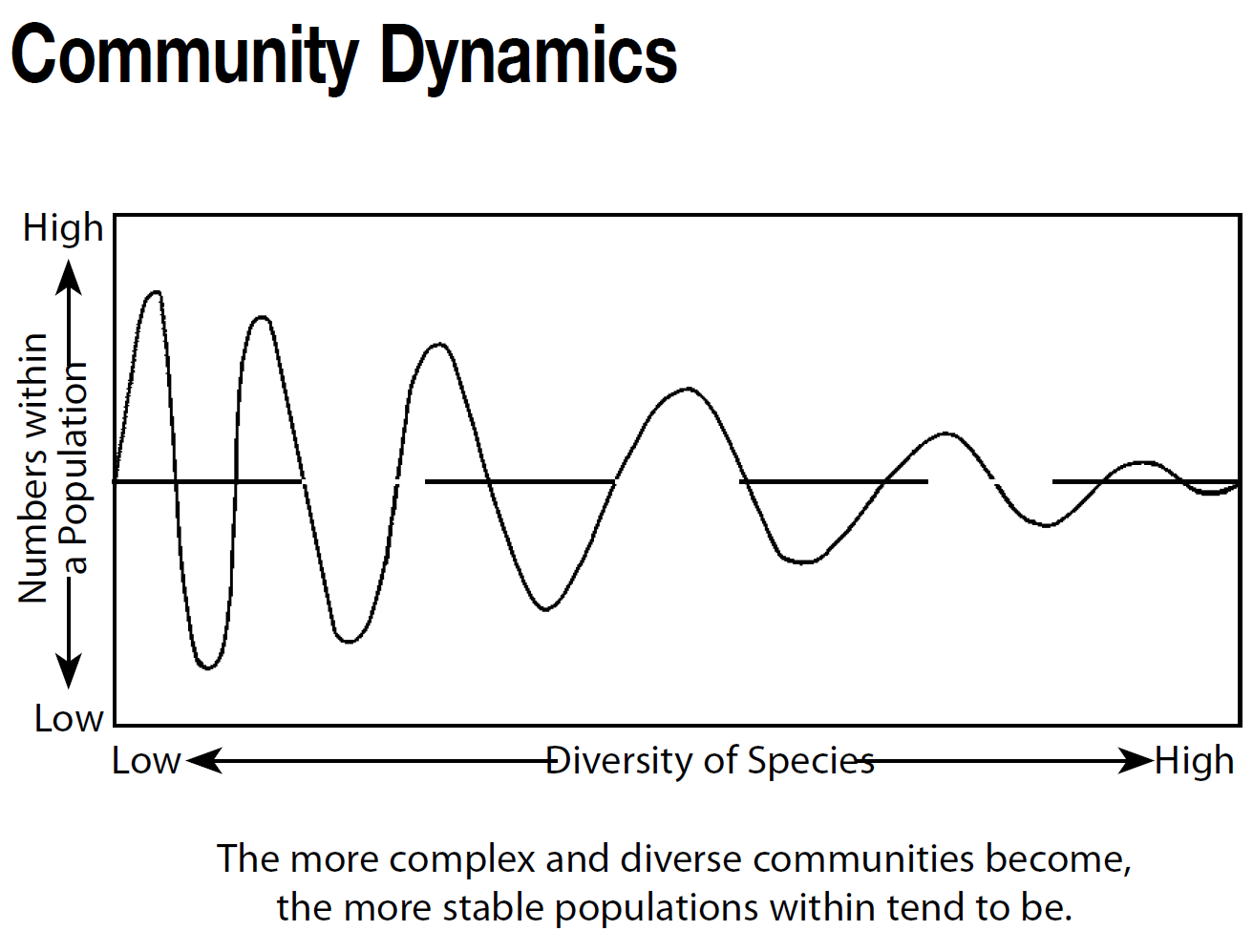

Figure 3. With few exceptions, natural communities strive to develop toward ever-greater complexity and, thus, stability. From unstable bare ground, where biological activity is low, stable range or forest communities develop over time. When humans reduce this complexity by planting monoculture crops or lawns, they defy the principles of nature so that they can only be maintained by unnatural means — and then only temporarily. As components within nature, humans cannot escape this principle any more than other organisms can.

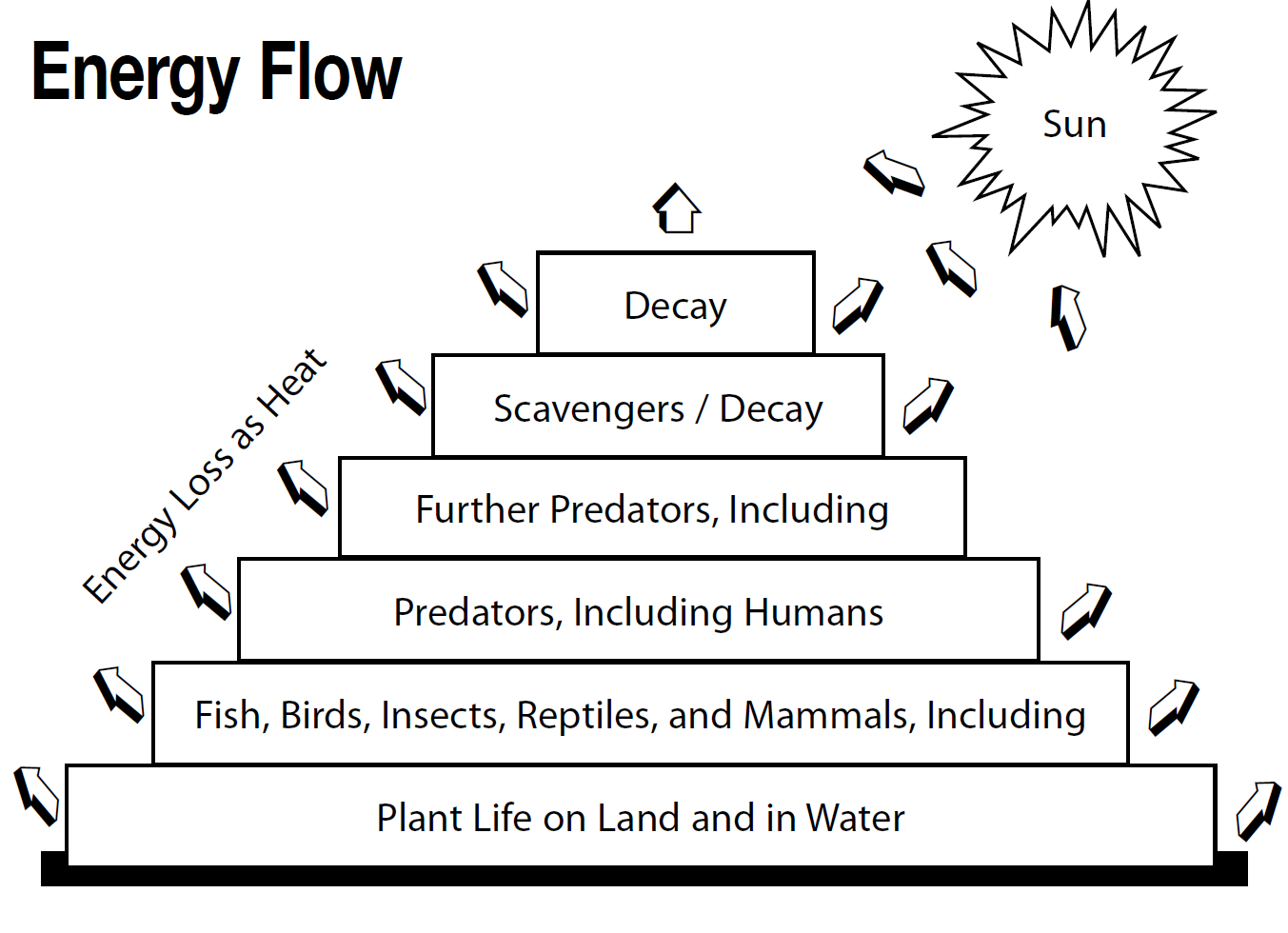

Figure 4. Almost all life requires the energy that flows daily from the sun. The basic conversion of this solar energy to usable form takes place through plant material on land and in water. That is why plants form the base of the energy pyramid depicted here. As the energy passes from plants to whatever eats them, and in turn eats the eaters of the plants, some energy is lost as heat; eventually, it is all used up: energy does not cycle; it flows through the ecosystem until it runs out.

1.1.2 The tools

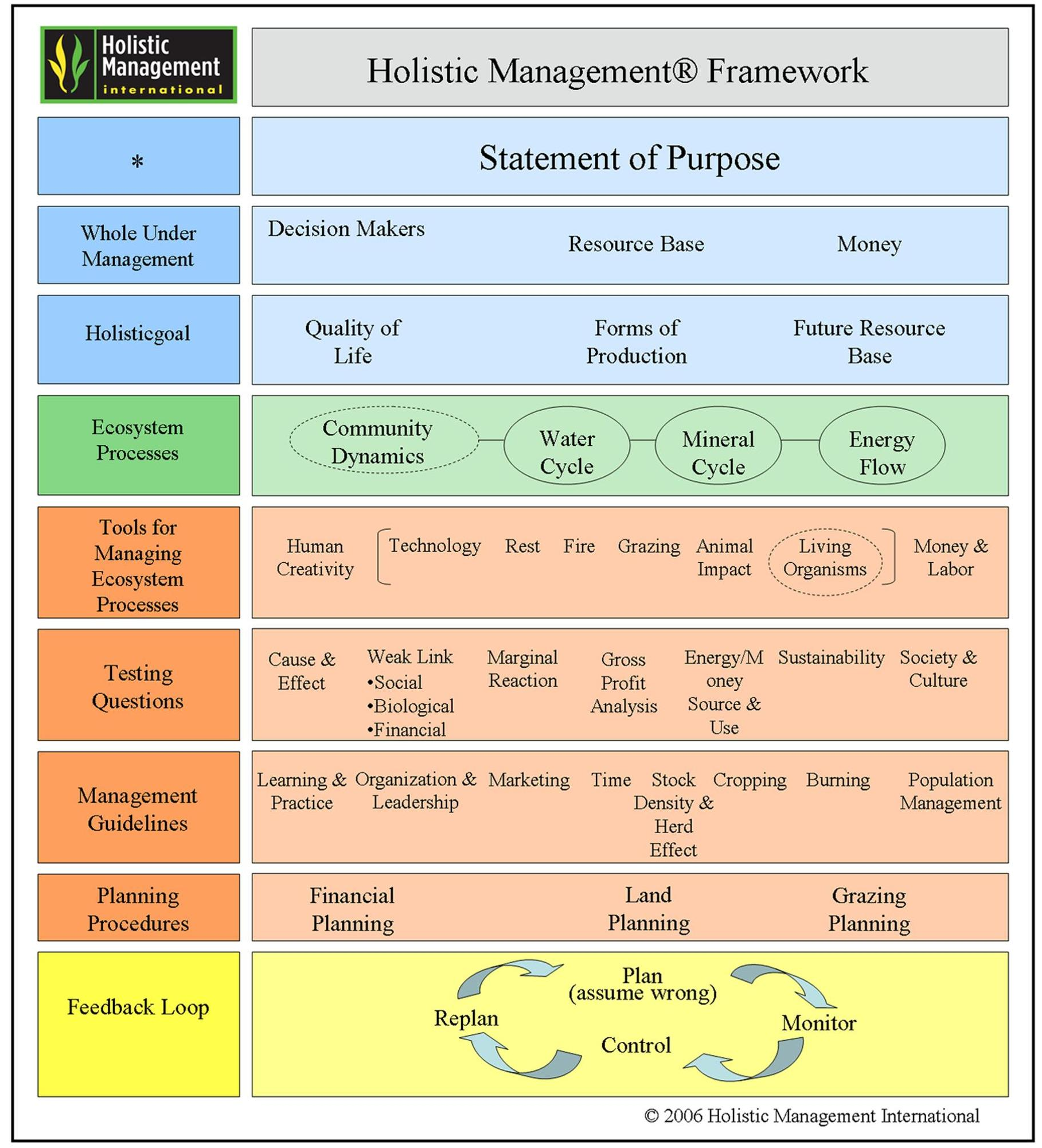

To review the tools that are available to us for managing ecosystems, we need to refer once more to the Holistic Management framework model.

Human creativity, as well as money and labour, bracket the other six tool headings in the model because both come into play in the use of the other tools.

Money and labour are listed together because the once simple combination of labour, creativity, and resources now frequently operate through the agency of money.

Inside the brackets are technology, rest, fire, grazing, animal impact, and living organisms. Those tools inside the brackets are the only tools (or categories of tools) that humans can use to modify ecosystem processes. One or both of the tools outside the brackets have to be used in association with the tools inside the brackets.[1,3]

The dotted line around living organisms in the tools line and around community dynamics on the ecosystem processes line reminds us that, when we use the tool of living organisms, we are, by default, affecting the dynamics of the biological community; they are the same thing.

Understanding the tools and their effect on ecosystem processes is essential for diagnosing a resource management problem.[3]

- Money and Labour: One or both of these tools is always required.

- Human Creativity: Key to using all the tools effectively.

- Fire: The most ancient tool.

- Rest: The most misunderstood tool.

- Grazing: The most abused tool.

- Animal Impact: The least used tool.

- Living Organisms: The most complex tool.

- Technology: The most used tool.

In conventional management, the tools available for altering any one of the ecosystem processes are limited to four broad categories: rest, fire, living organisms, and technology. In more brittle environments, however, these tools alone are inadequate to maintain or improve the functioning of the four ecosystem processes. Allan Savory identifies a remedy for this shortcoming in the behaviours of the large herding and grazing animals that have helped to maintain these environments for aeons.[1,3] Though the value of their dung for increasing soil fertility has long been recognised, many people still reject the most vital parts of the animals: their hooves and mouths. These can be harnessed as tools — animal impact and grazing — for improving water and mineral cycles, energy flow, and community dynamics.

When managing holistically, all tools are equal. No tool is inherently good or bad, and we cannot make judgments outside the context of the whole under management. Only when the holistic goal, the degree of brittleness of the environment, and other situational factors are known may a tool be judged as suitable or unsuitable. Careful consideration of the testing and management guidelines helps us to decide which tools are ultimately best to apply in a given situation. Even then, it’s healthy to assume that we might be wrong; therefore, we have to keep monitoring our tools to ensure that what we have selected is achieving what we want it to achieve.

Further reading:

- Savory, A & Butterfield, J. 1999. Holistic Management: A New Framework for Decision Making. 2nd edition, Island Press, Washington, DC.

- Savory, A. 2000. The Ecosystem Processes. In Holistic Management International: Getting Started with Holistic Management. Holistic Management International (HMI), Albuquerque, USA.

- Butterfield, J. 2000. Tools to Manage Ecosystems Processes. In Holistic Management International: Getting Started with Holistic Management. Holistic Management International (HMI), Albuquerque, USA.

© MB Equine Services 2014

www.mbequineservices.com

Follow Us!